From Contracts to Collaboration: What we’ve learned about water PPPs

- bluechain

- Dec 31, 2025

- 4 min read

Over the past few years, Bluechain has worked in a range of countries to support governments and utilities exploring and developing public–private partnerships (PPPs) in the water sector. These engagements have spanned very different institutional, economic, and social contexts, but the conversations have been strikingly similar. Again and again, the same opportunities, tensions, and learning points have emerged. What follows is a reflection on the most important lessons from this work. They are not theoretical insights; they are grounded in real projects, real constraints, and real debates about how water services can be delivered more sustainably.

PPP development requires a different mindset

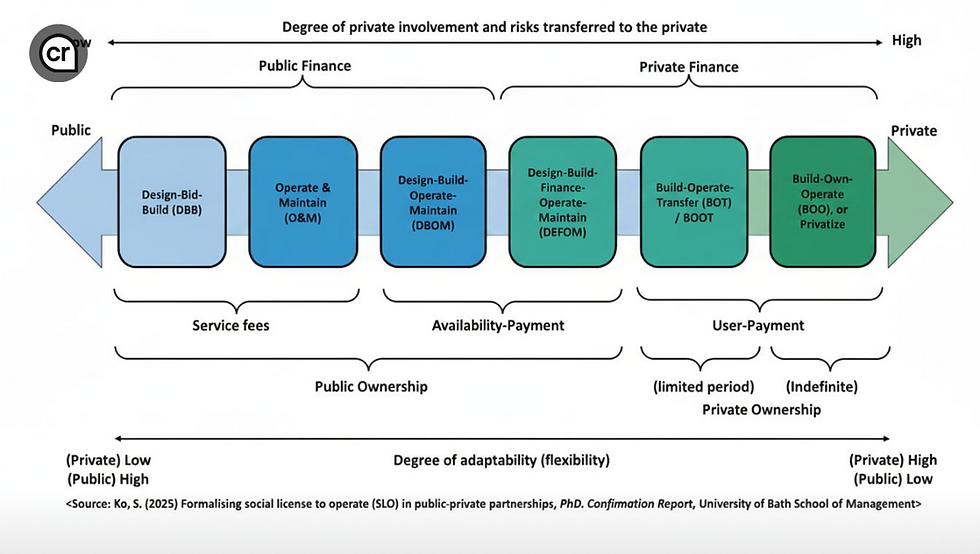

Perhaps the most important lesson is that developing a PPP is not just a technical exercise. It requires a shift in mindset that can be challenging in the water sector, where public provision has historically been the norm and where concerns around equity, affordability, and public control are rightly strong. A PPP is, at its core, a partnership. That means accepting that roles will change. Public authorities move away from directly delivering services and towards planning, regulating, and overseeing performance. Private partners take on responsibilities for delivery and, critically, assume certain risks in return for the opportunity to earn a return.

For colleagues who are new to PPPs, this can feel uncomfortable. The idea of sharing risk, costs, and profits is often misunderstood or viewed with suspicion. Our experience shows that people need time and structured support to understand what partnership really means in practice. Without this, PPPs risk being treated as outsourcing exercises or as a way to access private finance without meaningful risk transfer, both of which undermine their potential value.

PPPs are not suitable everywhere, and that is okay

Another strong lesson is that PPPs are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Not every project, utility, or country context is well suited to this approach, and recognising this early is a sign of good decision-making, not failure. A robust screening process is essential. This should look carefully at:

Whether the project has sufficient scale to justify the transaction costs involved

Whether there are willing and capable partners on both the public and private sides

Whether customers value improved services and are prepared to pay for them, at least partially

In some contexts, the political economy, affordability constraints, or institutional environment mean that a PPP is unlikely to succeed. In these cases, alternative delivery or financing models may be more appropriate. Being selective about where PPPs are pursued increases the chances that those that do move forward will actually deliver results.

Time and detail are not inefficiencies, they are investments

PPP development often takes longer than anticipated, and this can be a source of frustration for decision-makers under pressure to deliver results. However, one of the clearest lessons from our work is that being thorough early on pays off later. In the water sector especially, small assumptions can have big consequences. Understanding household willingness and ability to pay is not a box-ticking exercise; it is central to whether a project is financially viable and socially acceptable. Similarly, setting tariffs that are both commercially viable and politically feasible is one of the most complex challenges in PPP development. Equally important is stress-testing business models. Demand may grow more slowly than expected. Supply may be disrupted by climate shocks. Inflation, foreign exchange risks, or unforeseen events can significantly affect costs and revenues. Building and testing scenarios around these uncertainties is difficult and time-consuming, but it is fundamental to creating a robust and resilient PPP.

Be ambitious, but don’t let ambition delay progress

There is a natural tendency, especially in early PPP discussions, to focus on highly sophisticated financing structures or advanced management models. Ambition is important, and PPPs should absolutely be used to explore innovative financing solutions and new ways of working. At the same time, our experience suggests that starting with something is better than not starting at all. Waiting for the perfect structure, the ideal financing mix, or the most advanced contractual model can delay action indefinitely. In many contexts, it makes sense to begin with a simpler model and plan for greater complexity over time. PPP development should be seen as a journey. Early projects can build confidence, demonstrate value, and strengthen institutional capacity. More complex arrangements can then be introduced as experience grows and systems mature.

Capacity gaps are normal, and identifying them is progress

Every capacity assessment we have been involved in recent years has revealed gaps: gaps in technical knowledge, in financial modelling skills, in contract management experience, and in regulatory capacity. This is entirely normal, particularly in sectors and countries where PPPs are relatively new. What matters is not the existence of these gaps, but how they are addressed. It is far better to explicitly recognise what different stakeholders do and do not know than to assume capacity that does not exist. Once gaps are identified, they can be addressed over time through targeted support, partnerships, learning-by-doing, and institutional strengthening. Crucially, capacity constraints should not be a reason to abandon PPPs altogether. Instead, they should inform a realistic and phased approach to development.

PPPs are a tool, not a silver bullet

Finally, one of the most important lessons is the need for realism. PPPs will not solve all the challenges of delivering water infrastructure or sustaining services. They cannot compensate for weak governance, inadequate regulation, or a lack of political commitment to the sector. However, in the right context, PPPs can be a powerful tool. They can help crowd in private finance, bring in operational expertise, and improve service quality and efficiency. When designed carefully and implemented well, they can support more sustainable water services that better meet the needs of customers.

Our work on PPPs in recent year’s has reinforced that successful PPPs in the water sector depend as much on relationships, trust, and institutional learning as they do on contracts and capital. By adopting the right mindset, being selective and thorough, balancing ambition with pragmatism, and investing in capacity over time, PPPs can play a meaningful role in shaping more resilient and sustainable water systems for the future.

Comments